A Forgotten 16th-Century Manuscript Reveals the First Designs for Modern Rockets

The Austrian military engineer Conrad Haas was a man ahead of his time — indeed, about 400 years ahead, considering that he was working on rockets aimed for outer space back in the mid-sixteenth century. Needless to say, he never actually managed to launch anything into the upper atmosphere. But you have to give him […]

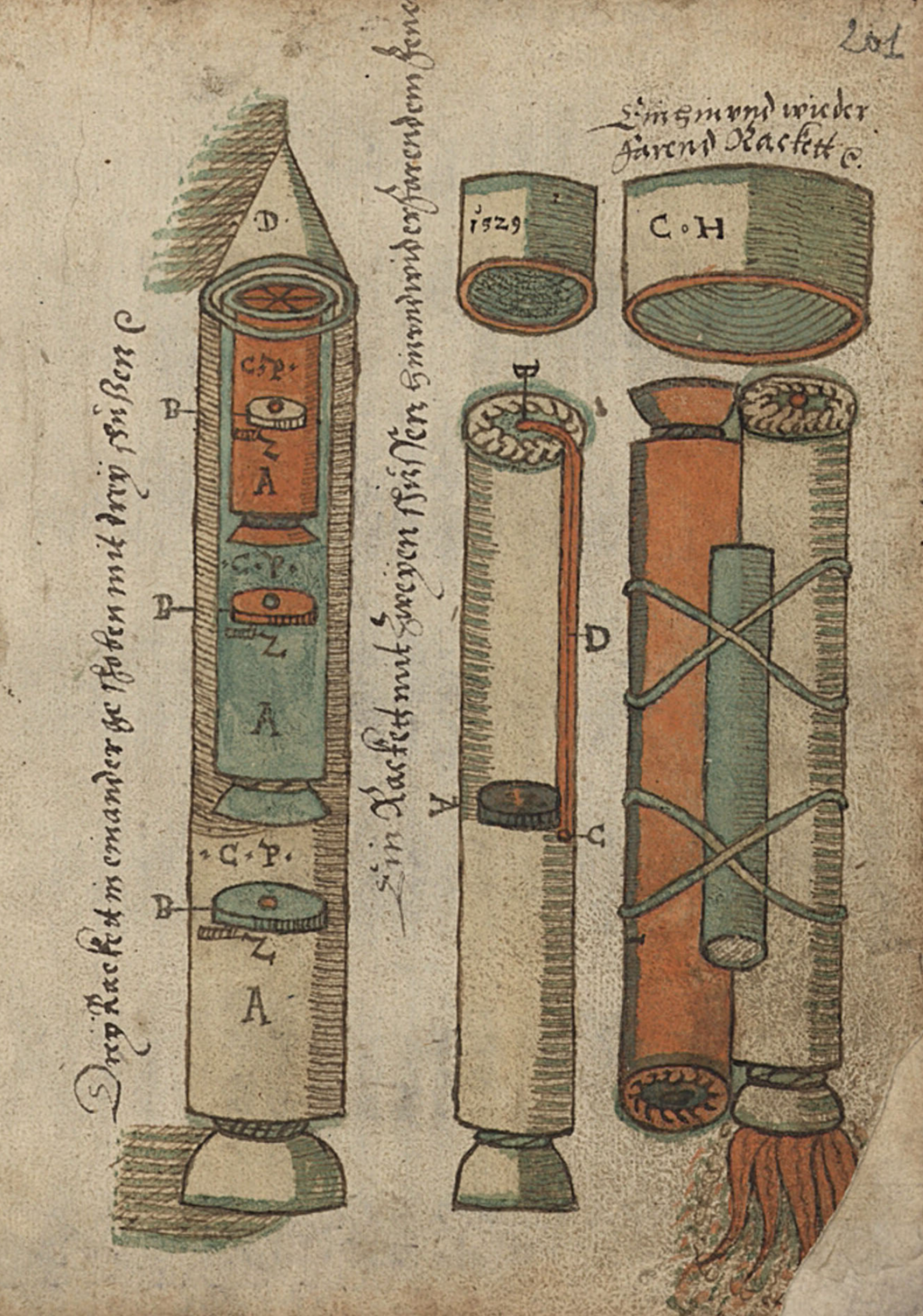

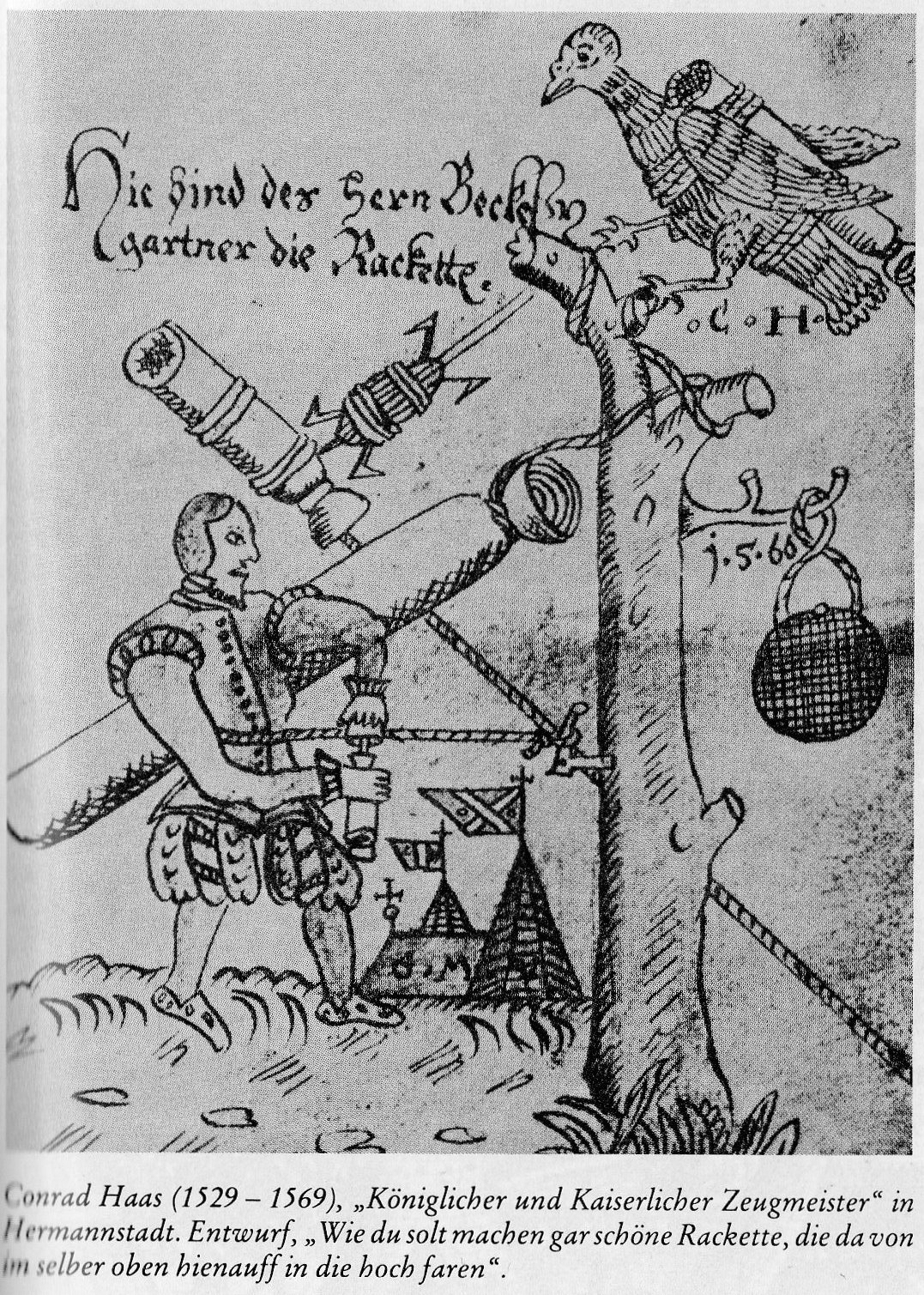

The Austrian military engineer Conrad Haas was a man ahead of his time — indeed, about 400 years ahead, considering that he was working on rockets aimed for outer space back in the mid-sixteenth century. Needless to say, he never actually managed to launch anything into the upper atmosphere. But you have to give him credit for getting as far as he did with the idea, a considerable progress documented in his treatise “How You Must Make Quite a Nice Rocket That Can Travel Itself into the Heights,” which no doubt sounds better in the original German. As Kaushik Patowary notes at Amusing Planet, its 450 pages are “filled with drawings and technical data on artillery, ballistics and detailed descriptions of multistage rockets.”

“Born in 1509 in Dornbach, now part of Vienna, to a German family from Bavaria,” Haas moved to Transylvania, then part of the Austrian Empire, early in his adulthood. “In 1551, Haas was invited by Stephen Báthory, the grand prince of Transylvania, to Hermannstadt (now Sibiu, Romania), where he became the commander of the artillery barracks and a weapons engineer.”

It was in this professional capacity that he began his research into rocketry, which led him to discover the concept of “a cylindrical thrust chamber filled with a powder propellant, with a conical hole to progressively increase the combustion area and consequently the thrust,” a clear intellectual ancestor of the multi-stage design “still used in modern rockets.”

Haas’ is the earliest scientific work on rockets known to have been undertaken in Europe. And until fairly recently, it had been forgotten: only in 1961 was his manuscript found in Sibiu’s public archives, which motivated Romania to claim Haas as the first rocket scientist. Though anachronistic, that designation does underscore the far-sightedness of Haas’ worldview. So do the personal words he included in his chapter about the military use of rockets. “My advice is for more peace and no war, leaving the rifles calmly in storage, so the bullet is not fired, the gunpowder is not burned or wet, so the prince keeps his money, the arsenal master his life,” he wrote. But given what he must have learned while living in politically unstable European borderlands, he surely understood, on some level, that it would be easier to get to the moon.

Related content:

Leonardo da Vinci Draws Designs of Future War Machines: Tanks, Machine Guns & More

Meet the Mysterious Genius Who Patented the UFO

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.