Microplastics Block Blood Flow in Mice Brains, Study Shows

As microplastics become more and more prevalent, even showing up in seafood, clouds and human testicular tissue, scientists are working to further understand how these plastic particles could impact ecosystems and human health. Based on a new study, scientists are now concerned about how microplastics could affect our brains after finding that the particles can […] The post Microplastics Block Blood Flow in Mice Brains, Study Shows appeared first on EcoWatch.

As microplastics become more and more prevalent, even showing up in seafood, clouds and human testicular tissue, scientists are working to further understand how these plastic particles could impact ecosystems and human health. Based on a new study, scientists are now concerned about how microplastics could affect our brains after finding that the particles can block blood flow in mice brains in the lab.

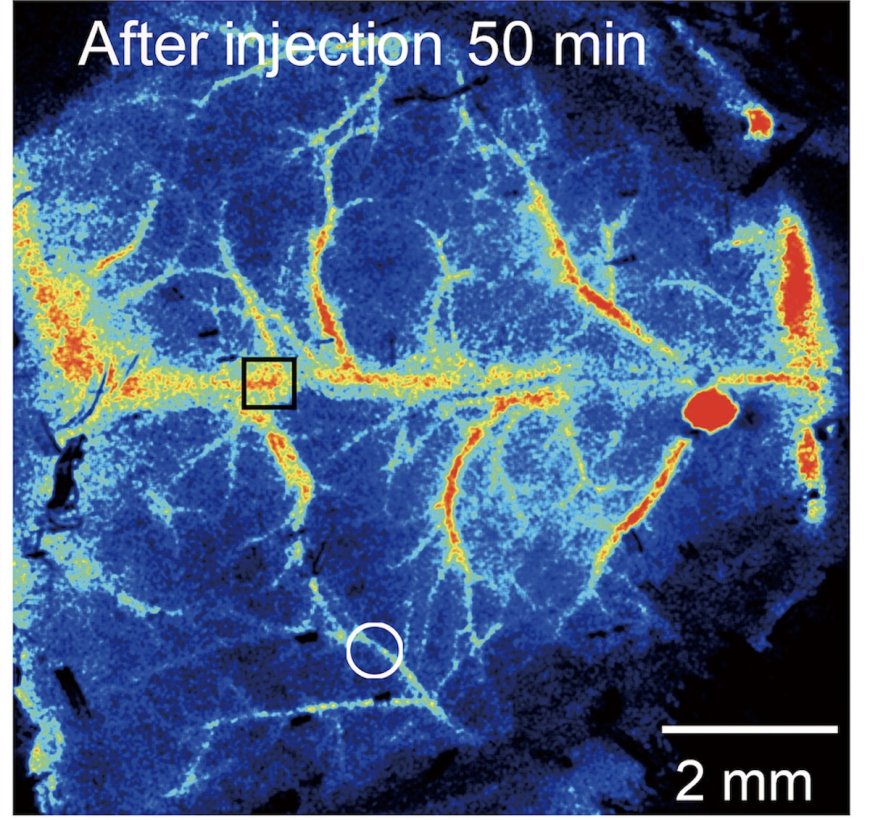

The study, published in Science Advances, involved the tracking of fluorescent polystyrene in mice blood and brains. The polystyrene, which is common in packaging like clear food containers and insulated beverage cups, was mixed with water and given to the mice. The researchers used miniature two-photon microscopy on mice to track the movement of the microplastics through clear screens placed in their skulls.

The researchers observed that the microplastics accumulated in immune cells, which then created blockages “like a car crash in the blood vessels,” Haipeng Huang, a biomedical researcher at Peking University in Beijing, said in a statement.

Sometimes, these blockages, which were similar to blood clots according to the research team, would clear on their own. However, other blockages remained for four full weeks.

Whether they lasted short-term or for the entire duration of the observation period, mice with microplastic blockages experienced reduced blood flow and moved slower and with less coordination compared to control mice, Yale Environment 360 reported.

The research team has also observed microplastic blockages in mice hearts and livers, but those studies have not yet been published.

The scientists also cautioned that while these results can bring up concerns over how microplastics may affect human health, the findings cannot conclusively be applied to humans because of the differences in blood circulation volume and vessel sizes between humans and mice. However, they did note that the research could provide foundational information for future studies.

“The potential long-term effects of [microplastics] on neurological disorders such as depression and cardiovascular health are concerning,” the authors stated. “Increased investment in this area of research is urgent and essential to fully comprehend the health risks posed by [microplastics] in human blood.”

According to a separate study published in April 2024, ingested microplastics were found to move from the human gut to the brain. Another study published in August 2024 further found microplastics in human livers, kidneys and brains, with alarming levels of these particles in the human brain samples.

In yet another recent study published this month, scientists determined that microplastics could pose risks to various human functions outside of the brain, including the respiratory system, the digestive tract and the reproductive system.

The post Microplastics Block Blood Flow in Mice Brains, Study Shows appeared first on EcoWatch.