PBS Documentary Shows Triumph and Tragedy in Fight for Water Rights

Water For Life began its journey when filmmaker Will Parrinello and his team followed environmental activist Francisco Pineda more than 14 years ago. Pineda was a winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize who was working to stop the development of a gold mine in his home country of El Salvador. “He doesn’t say this in […] The post PBS Documentary Shows Triumph and Tragedy in Fight for Water Rights appeared first on EcoWatch.

Water For Life began its journey when filmmaker Will Parrinello and his team followed environmental activist Francisco Pineda more than 14 years ago. Pineda was a winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize who was working to stop the development of a gold mine in his home country of El Salvador.

“He doesn’t say this in the film, but he says regularly – you can’t come here and destroy our precious water resources and our ways of life,” said Parrinello. “We’re happy as subsistence farmers. Yes, of course, we want better lives for our children. We want them to have better education. We want better health care. But we’re quite honestly happy with our lives here as farmers.”

Francisco Pineda harvesting corn. Will Parrinello

However, as he continued to film Pineda and his community’s fight over five years, funding dried up. Parrinello and his filmmaking partner decided to expand the story.

“Why don’t we put together three stories that show these patterns of exploitation and impunity that are happening throughout Latin America and are emblematic of the same kinds of stories that are happening around the world — Africa, Asia, the Pacific and even now in North America?” he said.

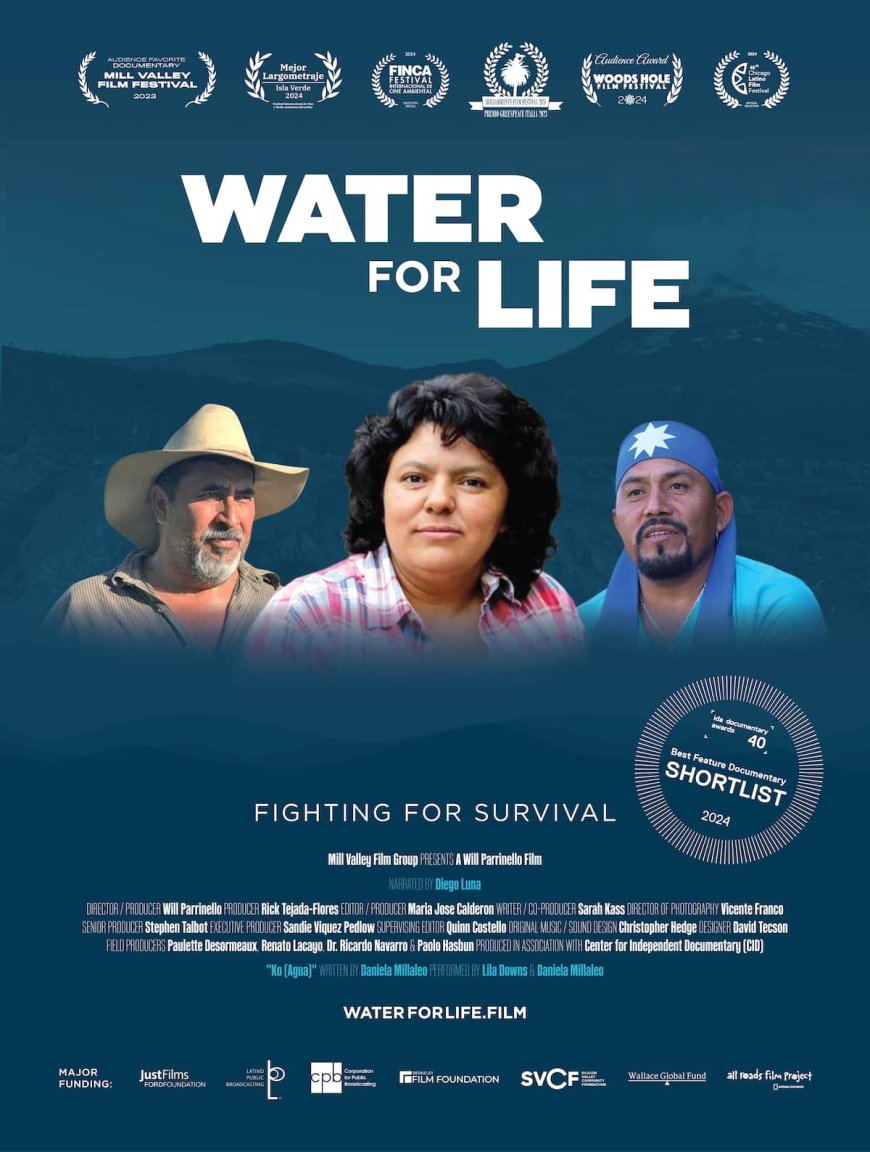

The result is the long-form documentary Water For Life which intertwines Pineda’s story in El Salvador with that of Alberto Curamil, a Chilean activist fighting against a hydroelectric dam that would irreparably harm the Cautin River that runs through Mapuche Indigenous lands, and Berta Cãceres of Honduras, also fighting for water rights. The film is narrated by actor Diego Luna.

In each case, the protagonists and their supporters are fighting to maintain access to clean water, either for themselves, their livestock or their crops. At one point in the film, Curamil is arrested on fake charges, and both Pineda and Cãceres have their lives threatened.

As a filmmaker and environmentalist, Parrinello has seen an increased emphasis on water rights.

“There’s this push on the part of large corporations to want to privatize water because it’s an incredible resource and there’s a lot of money to be gained,” he said. “The grassroots movements have succeeded in stopping that from happening on a large scale. I’m not sure how long they’ll hold out, because that commodity is becoming more precious as we face climate change.”

The film exposes some of the corporate pressures exerted on these communities, and how some of these companies strategize to divide the community, even sending spies into the activist movements.

Spoiler alert: Water For Life does reveal these three campaigns as success stories. The dam is not built in Chile, and in Honduras, the DESA corporation fails in its effort to build a hydroelectric project. In El Salvador, Pineda’s campaign not only helped institute a mineral mining ban in the country, but the country also won a $350-million-plus lawsuit brought by the Pacific Rim corporation.

But the mineral mining ban that had been put in place in El Salvador was reversed by the country’s lawmakers in late 2024, allowing again for the extraction of gold. Francisco Pineda has been recently sending Parrinello videos of trucks in El Salvador, representing companies from Peru, China and Canada. The exploration of new mining sites has begun in El Salvador.

“I’m quite frankly concerned for Francisco Pineda’s safety,” Parrinello said. “But he said, ‘Listen, we’re adults. We know what we’re doing. This is what we do. We’re not going to stop now.’”

And safety is an issue covered in the film. Berta Cãceres is murdered during the time of the filming, an act which has been attributed to people affiliated with DESA, including David Castillo, the former president who was found guilty and is serving a 22-year sentence. Honduras is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for environmental activists.

Berta Cãceres in the Rio Blanco region of western Honduras where she, COPINH (the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras) and the people of Rio Blanco have maintained a two-year struggle to halt construction on the Agua Zarca Hydroelectric project that poses grave threats to local environment, river and Indigenous Lenca people from the region. Courtesy Goldman Environmental Prize

“What they do and who they are is quite real. We’ve experienced it. We’ve seen their courage firsthand. We were in situations where we were frightened, and if they were, they barely showed that,” Pineda said.

Cãceres’ death had an effect not just on the movement, but on Parrinello as well.

“I kind of sunk into a depression. We talked to the family. We talked to her daughters and questioned whether we should go on. And they were like, ‘Are you kidding me? You have to go on. Of course you have to go on. You guys are storytellers,’” he said.

Berta’s three daughters have taken up the mantle of her work. Her daughter is part of the non-profit that Berta and her husband started. Berta’s daughter Bertita is the Director of COPINH, the Indigenous rights organization founded by her parents, her sister Laura is an Organizer at COPINH and their older sister Olivia, once a Congresswoman, is now the Ambassador to Cuba.

In an attempt at journalistic balance, Parrinello attempted to interview Thomas Shrake of Pacific Rim. Shrake had expressed the desire to mine for gold in a way that was environmentally and socially responsible, which Parrinelli appreciated, but they couldn’t secure an interview.

“He refused to do it. He said he just had so much more to lose than to gain,” Parrinello said.

But bringing attention to the plight of activists in Latin America was one of the main reasons to make the film.

“Global Witness has been tracking the murder of environmental and human rights activists, I think, since 2012. And I think it’s up to around 2700 people have been murdered in that time,” he said. “That kind of impunity and violence to me was stunning. That’s a way to look at what corporations are doing that perhaps our retirement accounts are invested in and say, is this acceptable? Do we feel good about this? Do we feel good about what our government is doing? I thought that was really, really important.”

Parrinello has been making films about Goldman Environmental Prize winners for the last 21 years. All three of the main characters in Water For Life are Goldman prize winners.

Alberto Curamil is an Indigenous Mapuche Chief in Chile who, along with fellow Mapuche leaders and community members, fights to protect his ancestral land from corporate development that threatens their sacred river. Majo Calderon

“What I’ve learned being around the protagonists in my film is that it takes that kind of committed dedication to create change,” Parrinello said. “And because they all do it on a grassroots level, beginning with their neighbors in their own community, I’ve seen that they gain strength, and they gain a certain courageous perspective because they know they’re supported by so many people.

“And those movements, like all grassroots movements, if they gain traction, it goes from local to regional to national movements. And that’s what we saw.”

The post PBS Documentary Shows Triumph and Tragedy in Fight for Water Rights appeared first on EcoWatch.